Session 2: Religious Liberty & Slavery

In the Antebellum era, the religious lives of enslaved people were pervasively surveilled and regulated by the state and by enslavers. In this session, learn how “slaveholders’ religion” justified chattel slavery, and how both the law and Christian theology changed over time to ensure that, for Black people, “freedom in Christ” did not necessitate freedom from slavery.

About the speakers

Audra Lyn Savage interrogates race and racism in law, specifically focusing on critical race corporate law, as well as law, race & religion. She teaches courses on business organizations, mergers & acquisitions, and critical race theory. Professor Savage's scholarship has been published in the Columbia Law Review Forum, Utah Law Review, and the Journal of Law and Religion. She also has a chapter in a peer-reviewed collection of essays on Derrick Bell's racial realism. Professor Savage is the recipient of the 2020 Innovation, Business and Law Center Prize from the University of Iowa College of Law, and the Gertie & John Witte Prize in Law & Religion (2018).

The Rev. Kelly Brown Douglas, Ph.D., is Interim President of the Episcopal Divinity School. From 2017 to 2023, she was Dean of the Episcopal Divinity School at Union Theological Seminary and Professor of Theology. She was named the Bill and Judith Moyers Chair in Theology at Union in November 2019. She also serves as the Canon Theologian at the Washington National Cathedral and Theologian in Residence at Trinity Church Wall Street.

Douglas is the author of many articles and six books, including Sexuality and the Black Church: A Womanist Perspective, Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God, and Resurrection Hope: A Future Where Black Lives Matter, which won the 2023 Grawemeyer Award in Religion. Her academic work has focused on womanist theology, sexuality, and the Black church.

Plantation Funeral, (John Antrobus ca. 1860).

Key Takeaways

Enslaved people were denied all constitutional rights–including the right to religious liberty. A myriad of state laws barred or regulated enslaved people from, among other things, gathering together for worship or religious rituals, preaching or exhorting, and reading the Bible.

While early English common law suggested that Christians could not hold other Christians as slaves, the colonies quickly passed laws to ensure that conversion or baptism did not compel an enslaved person’s freedom, therefore protecting enslavers’ right to human property.

Even amidst slavery, Black people “stole away” to practice a range of religious traditions. In addition to Islam and indigenous African religions, enslaved peoples developed starkly different Christian theologies than the “slaveholders’ religion” practiced by most Southern whites.

Reflection Questions

Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison famously burned a copy of the Constitution, calling it a “covenant with death” and “agreement with hell” because it protected slavery. In this session, the speakers argue that racism is “in the DNA” of the country. Is the Constitution–including the religion clauses of the First Amendment–still tainted by the legacy of slavery? If so, what, if anything, might be done to redeem it?

Enslavers and enslaved people practiced very different forms of Christianity. Where can you see remnants of both these religious traditions today?

How should the Supreme Court account for the history of slavery in its current approach to the First Amendment, which looks to American “history and tradition” to interpret modern disputes?

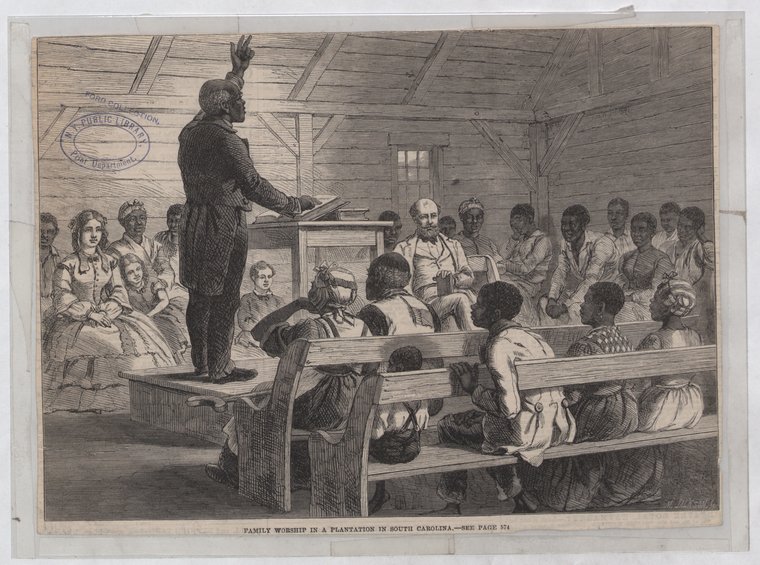

Family worship in a plantation in South Carolina (Frank Vizetelly 1863), The New York Public Library.

Further Reading

Audra Lyn Savage, The Religion of Race: The Supreme Court as Priests of Racial Politics, Utah Law Review (2021)

Kelly Brown Douglas, Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God (2015)

Albert J. Raboteau, Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South (1978)

Charles Irons, The Origins of Proslavery Christianity: White and Black Evangelicals in Colonial and Antebellum Virginia (2008)

Watched this session of the curriculum and have some thoughts? We’d love to hear from you.